In the silent darkness between stars, a new astronomy was born on September 14, 2015, when LIGO’s twin detectors registered a chirp—a whisper from two black holes colliding a billion light-years away. That moment didn’t just open a new window on the universe; it quietly set in motion a revolution in how we measure cosmic distances. For decades, astronomers have relied on standard candles—familiar objects like Cepheid variables and Type Ia supernovae—to gauge the scale of the universe. But now, gravitational waves are emerging as a powerful new ruler, one that requires no assumptions about brightness or chemistry, only the immutable laws of general relativity.

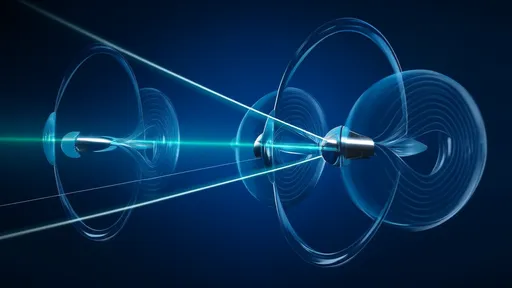

The principle is as profound as it is simple. When two compact objects—black holes or neutron stars—spiral into each other, they ripple spacetime itself, sending out gravitational waves that can be detected on Earth. The amplitude of these waves directly encodes the distance to the source. Unlike light-based methods, which depend on understanding the intrinsic luminosity of a source, gravitational wave signals provide a direct, physical measurement of how far away the event occurred. There is no calibration, no cosmic ladder to climb—just pure geometry.

This isn’t just an incremental improvement. It’s a paradigm shift. Traditional standard candles, for all their utility, come with systematic uncertainties. Interstellar dust dims starlight; metallicity affects the behavior of Cepheids; even Type Ia supernovae show subtle variations that complicate distance estimates. These errors propagate, limiting the precision of key cosmological parameters, most notably the Hubble constant—the rate of the universe’s expansion. Gravitational waves bypass these issues entirely. They do not dim. They are not absorbed. They travel virtually unimpeded across cosmic distances.

The real breakthrough, however, comes when gravitational waves are combined with electromagnetic observations. The 2017 detection of the neutron star merger GW170817 was a landmark event. Gravitational wave observatories pinpointed the distance; optical telescopes identified the host galaxy and measured its redshift. In one stroke, astronomers obtained a direct, independent measure of the Hubble constant. The result was consistent with previous estimates but, more importantly, it came with a different set of assumptions—and different systematics. This cross-validation is the heart of the precision revolution.

As the network of gravitational wave detectors grows—with LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA now joined by LIGO-India in the planning stages—the number of detectable events is skyrocketing. Each neutron star merger, in particular, offers a chance to measure distance and redshift independently. Statistically, as the catalog of such events grows into the hundreds, the uncertainty in the Hubble constant is expected to shrink to below 1%, a level of precision that could resolve the current tension between early- and late-universe measurements.

But the implications go far beyond the Hubble constant. Gravitational wave standard sirens—as they are aptly named—provide a test of general relativity on cosmological scales. They allow us to probe the large-scale structure of the universe and the nature of dark energy without relying on the traditional distance ladder. In the era of multi-messenger astronomy, they serve as anchor points, grounding the cosmic scale in fundamental physics.

Yet challenges remain. Gravitational wave detectors are sensitive to mergers only within a certain range, and pinpointing the host galaxy requires rapid follow-up with telescopes. Future observatories, like the space-based LISA mission, will extend this range to include massive black hole mergers, providing standard sirens across vast cosmic epochs. This will open a new frontier: tracing the expansion history of the universe directly, from the local neighborhood to the high-redshift universe.

The quiet chirp of colliding black holes has set off a loud revolution. In the subtle distortions of spacetime, we are finding a new way to map the cosmos—one that is direct, model-independent, and deeply rooted in theory. As detectors improve and events accumulate, gravitational wave cosmology is poised to deliver not just new precision, but new clarity in our understanding of the universe’s size, age, and ultimate fate.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025